The Cuban-born son of an Irish father, O'Farrill composed or arranged

for (among others) Benny Goodman, Machito, Dizzy Gillespie, Bola de Nieve,

Charlie Parker, Israel "Cachao" Lopez and Count Basie. He wrote some of

the definitive compositions of Latin jazz, and was part of the music's

birth in the 1940s and '50s, part of the mambo and big band eras. But

for most of the last 30 years, he opted for the financial security of

writing commercials, removing himself from the music he loved. While he

remained a legend among Cuban and jazz musicians, the larger world of

pop culture doesn't even know he exists.

O'Farrill is philosophical about this. "Jazz is not a commercial music,"

he said by phone from his apartment on New York's Upper West Side. "Yes,

sometimes I felt very frustrated that I couldn't do the music I loved

and make money at it, felt that persons in positions of power were blind.

I finally said to hell with it, I'm gonna go into the commercial field

and make money. But I didn't obsess about it."

But now O'Farrill is getting a final chance at recognition with Heart

of a Legend (Milestone Records), an overview of his life's work that

features some of the best musicians in Latin jazz today: Gato Barbieri,

Cachao, Paquito D'Rivera, Arturo Sandoval, Juan Pablo Torres, Carlos "Patato"

Valdes, Alfredo "Chocolate" Armenteros, and many more. He is touring with

his big band again. This Wednesday he will be celebrated at a party hosted

by talk-show queen Cristina Saralegui and actor Edward James Olmos at

the new Cafe Nostalgia in Miami Beach, at one of those model- and celebrity-laden

affairs usually awarded to young pop stars with pretty faces and sales

in the millions.

"I never lost the hope that maybe it would happen some day," O'Farrill

says. "It feels great, just great. Working with such great musicians and

being able to do the material however I liked, that was a very precious

thing."

The man behind Heart of a Legend is executive producer Jorge

Ulla, a Cuban-born filmmaker who made Nobody Listened and Guaguasi

(for which O'Farrill composed the soundtrack), and who has a successful

commercial production company -- which is how he met O'Farrill more than

20 years ago.

Ulla remembers hearing Dizzy Gillespie praise O'Farrill at a birthday

party the Cuban saxophonist D'Rivera threw for the older Cuban years ago.

"Dizzy said 'I owe this man half of what I am,' " Ulla said. So the

record was a labor of love for him. "I am doing well, but not that well

[financially] -- but this was a kind of cultural rescue," Ulla said. "I

always looked at Chico as an equal to not just Machito or the other greats,

but also to the Lecuonas [Ernesto Lecuona is the island's equivalent to

George Gershwin.] Look at what he did in Cuban music, there at the crossroads,

influencing everyone. I remember Ruben Blades saying if this man hadn't

done what he did, salsa wouldn't have been what it was. Other musicians

had enormous respect for him. But he never got the attention that he deserves."

In 1995, Ulla thought O'Farrill's chance had come when he made Pure

Emotion with respected jazz producer Todd Barkan (who also produced

Legend), and the record was nominated for a Grammy for Best Latin

Jazz Album. But Brazilian legend Antonio Carlos Jobim, who died that year,

got the award instead. "I saw this sadness in Chico, though of course

he didn't say anything, and I said, 'The story's not over yet.' "

O'Farrill fell in love with jazz in classic American style, as a rebellious

teenager. His parents sent him from Havana for misbehaving to military

school in Georgia, where he heard Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller, bought

a trumpet and joined the school band. An inscription in his high school

yearbook reads "To a master of the Rumba -- Learn to appreciate swing!"

Back in Havana, O'Farrill played with important groups like Armando Romeu's

orchestra and the Lecuona Cuban boys, and studied composition.

But his island's music didn't do it for him. "Cuban music at the time

was boring to me," O'Farrill says. "Jazz was refreshing and exciting."

New York and bebop beckoned, and in 1948 O'Farrill, like so many eager

young artists before and since, left for the Big Apple. It was there that

he rediscovered his culture. "Cuban music became very exciting for me

later on, for one reason -- because of Machito and the marriage of jazz

and Cuban music," O'Farrill says. "That made Cuban music richer harmonically

and more exciting. It was the beginning of Latin jazz."

The late 1940s and early 1950s saw the confluence of Cuban rhythms and

American big band orchestration that would produce mambo, the dominant

pop music of the 1950s. It also saw the mix of bebop jazz and Afro-Cuban

music called Cubop -- the first Latin jazz, with musicians like Charlie

Parker, Flip Phillips and Dizzy Gillespie coming together with Cubans

like conguero Chano Pozo and Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra, directed

by Mario Bauza. O'Farrill was at the nexus of this musical fusion, bringing

his formal training and rich musical sensibilities to bear on composing

or arranging for people such as Gillespie and Machito. He married Cuban

feeling and rhythm with jazz harmony, color and structural innovation.

He says he can't explain or analyze why these musicians came together,

or why he was compelled to link the two forms of music. "People are attracted

to each other when they have similar ideas," O'Farrill says. "We would

just go out looking for what we wanted. I was trying to put the bebop

idiom, the jazz idiom, into Cuban music. That was my natural way of expressing

myself. It just came out -- I didn't say 'I'm gonna do this or that' intentionally,

it just came out because that's the way I felt."

"Chico never thought much of Cuban music until he came to America to

become a jazzman, when he realizes that the music he thumbed his nose

at at home is the one that is making noise in jazz," says Nat Chediak,

an Afro-Cuban jazz aficionado who has written a dictionary of Latin jazz.

"He was the first one who put [Afro-Cuban jazz] in black tie and tails,

who expanded it beyond a novelty. He brought respectability to Afro-Cuban

jazz and took it away from being a trend. It wouldn't have gone beyond

that if it weren't for him."

His life is musical history. He got his nickname because Benny Goodman

couldn't pronounce Arturo, and so labeled him Chico, which O'Farrill says

all Cubans were called then. He recalls another jazz legend during the

recording of his Afro-Cuban Jazz Suite, one of the era's definitive compositions,

for the Verve label in 1950. When saxophonist Fats Navarro didn't turn

up, Charlie Parker was called in as a last-minute substitute. "He said,

'Chico show this to me,' and he played it right away like he'd been playing

it forever," O'Farrill remembers. "My mouth was just hanging open -- I

was ready to faint."

For musicians back in Havana, O'Farrill's success on the American jazz

scene was inspiring. D'Rivera -- whose father had a music store where

O'Farrill, Cachao and Ernesto Lecuona used to buy bass strings and music

paper -- remembers how they followed O'Farrill's career through his recordings

and a Voice of America program called The Jazz Hour, and looked

up to him as one of their own who had become important in American music.

"He was very important for us in Havana, he was like a legend," D'Rivera

said. "Always we talked about Chico the Cuban who wrote music for Stan

Kenton and Count Basie and Benny Goodman."

But O'Farrill's role of composer and arranger was one that naturally

kept him in the background, as well as what those who know him say is

a natural modesty and reticence. He left the United States in 1956, as

mambo was peaking in popularity, first spending time in Havana, and then

a decade in Mexico City. When he returned to the States in the mid-'60s,

rock and roll ruled, and though he worked for the Count Basie big band

and people like Cal Tjader and Clark Terry, O'Farrill's skills, and the

jazz music he loved -- which has never had the broad commercial appeal

of simpler pop musics -- were no longer in demand. So he retreated into

the financial security and creative wasteland of commercial jingles.

D'Rivera says that was a pity, both for O'Farrill and for the music.

"He spent too much time in the commercial field, for personal and economic

reasons. We could have had more of him out there for a longer time. So

the price he had to pay is no recognition. I regret that because we love

him so much and have so much respect for him, and other people with a

lot less talent got a lot more recognition. But you have to fight for

your own rights too -- no one is going to fight for you."

"I think he regrets some of the choices he made," Ulla says. If so,

O'Farrill is too much of a more reticent, well-mannered age to complain

or make excuses.

"I hate to tell you this, but I'm 78," he says. "I don't like that,

but what can I do? All your days should be endured with grace. It's the

only way to live."

So he is thoroughly enjoying his late brush with fame. His Chico O'Farrill

Big Band, led by his son Arturo, just toured in Mexico and will perform

on the West Coast soon. These days he's got fans like movie star Matt

Dillon, who Ulla says called O'Farrill recently to advise him on his health.

"I called Chico yesterday and he said, 'Jorge, you know what happened?

Matt Dillon called, and he said he has a Cuban doctor for me, who has

a lot of herbs. You know what? I think he's recommending a Santero.' "

Ulla says the fact that so many people have come together for his music

has given O'Farrill a new lease on life -- and hopefully on the life of

his music as well. "There's a new energy and vitality to what he's done

here, and it's not gonna go into a black hole," Ulla says.

Typically, O'Farrill doesn't say much. "He's a very private man," Chediak

says. "But I know that he's very emotional. For someone of his age and

professional stature, it's not all in the metronome or on the page, it's

in the heart."

His fellow musicians, however, are happy to say it for him. "He deserves

all the love and recognition we can give him," says D'Rivera. "I'm glad

he's back home where he belongs."

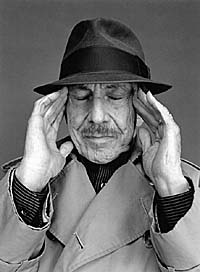

O'FARRILL, O'FINALLY

Forgotten for decades, Cuban jazz composer

Chico O'Farrill finds himself on the edge of fame once more, just as he's

pushing 80.

Music is fickle and indiscriminate. Fame comes rarely, and it doesn't always

come to those who merit it most, and it doesn't always come at the right

time. For Arturo "Chico" O'Farrill, 78, one of three men who made the marriage

between American jazz and Afro-Cuban music, whose influence still sounds

in salsa and Latin jazz today, recognition is coming at the end of his life,

after almost eight decades and after he had almost given up on making music.

'All your days should be endured with grace. It's

the only way to live.'

'All your days should be endured with grace. It's

the only way to live.'

CHICO O'FARRILL